An early travel route that shaped history

Fig 1. 3D Map. The Road to Cumberland followed natural pathway between Parrsboro and Minudie. Source Maphill 3D Map

Click on images on this page for larger versions

“The Road to Cumberland” was an early travel route across the Chignecto Peninsula in Cumberland County.

The story behind this overland route encompasses geological events and human activities with the Ottawa House and Partridge Island forming an integral part of the historical account. As with all communities on the Upper Bay of Fundy, the history of this route has both a regional and an international context.

My initial version of this account was prepared for the Ottawa House Historical Society some years ago. It draws on original maps, photographs, letters and other archival materials, property deeds, land grants and probate records.

– Kerr C.

The Minudie to Partridge Island Route

The interior of the Chignecto Peninsula contains several sets of valleys that form natural pathways that cross the peninsula from north to south (Fig.1 above). Shaped by glaciers from the last Ice Age, the landscape was made up of interior waterways that required minimal construction to make them passable for human transport. One such overland conduit ran between the present-day communities of Minudie and Parrsboro. Since it was conducive to travel, it was only natural that starting with the arrival of the earliest inhabitants to Nova Scotia, it was used for passage both on water and land.

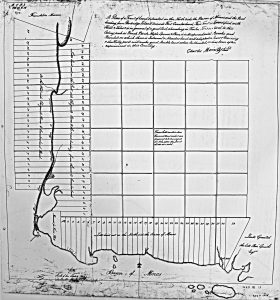

At least three distinct groups used the route: the Mi’kmaq, the Acadians and the English. Each of these groups may have given the route a name; however, for the purpose of this description, it will be referred to as the Road to Cumberland. This name can be located on various deeds and surveyor’s maps (e,g, as in Fig 2) prepared for the English who were granted land along the route several years after the expulsion of the Acadians.

The significance of the name “Cumberland” may pertain to at least three important events that occurred shortly after the founding of Halifax in 1749.

The first of these dates to the same year as the Grand Dérangement in 1755 when Fort Beauséjour was surrendered to the English. Fort Beauséjour was a French fort located on the Aulac Ridge overlooking the Cumberland Basin; on June 4, 1755, the fort was attacked by a group of British regulars and New England militia under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Monckton. On June 16, 1755 the French surrendered and the English took control of the fort and re-named it Fort Cumberland. The fort became a military emplacement that guarded British interests in this region of Nova Scotia for years to come. Its strategic location allowed for the control of the Isthmus of Chignecto where an overland travel route extended from what is present-day New Brunswick (New Brunswick was established on August 16, 1784) to peninsular Nova Scotia.

The two other events involving the name Cumberland occurred shortly after Louisburg fell to the English in July of 1758. England quickly decided that it was now important to place more settlers in the Colony of Nova Scotia and instructed Charles Lawrence, (Conrad, p.17 and Murphy, p.56) the governor of the province at that time, to take the necessary steps to attract settlers. Before the fall of Fort Beauséjour and Fort Louisburg, Nova Scotia had received only two substantial groups of colonists. One group of settlers arrived with Cornwallis in 1749 and founded Halifax; the so-called Foreign Protestants of Nova Scotia who arrived between 1750 and 1752 formed the second group. Since these groups lived mostly in Halifax and Lunenburg, Governor Lawrence was expected to place English-speaking settlers in other parts of the province; this was especially true for the fertile lands vacated by the Acadians when they were forcibly removed in 1755.

One of the first steps taken by Lawrence and his Council was the establishment of five counties in 1759 (Ferguson 1966, p.14). The boundaries and the names of the counties are shown in Fig.3; the newly formed county of Cumberland appears at the top of the map. Its boundaries are very different from those of today and from the map one might think that Cumberland County was initially very small. However, quite the opposite is the case. When Cumberland County was created, it included all of present-day New Brunswick and possibility more. Portions of Maine and Quebec may have been part of the county in 1759 because the location of its western and northern boundaries is largely unknown.

Before settlers could be given land, Lawrence and his Council had to create townships and establish their boundaries. The townships created in 1761 are shown on Fig.3. Notice that Cumberland County was given three townships and that one was called Cumberland Township (Wright, 1946). Thus, by 1761, a traveler could start at Partridge Island and take the Road to Cumberland to reach Cumberland County, Cumberland Township, and Fort Cumberland.

The Location of the Ottawa House on a Network of Travel Routes

The historical significance of the Ottawa House and Partridge Island stems largely from their location on the Road to Cumberland. The fact that the Road to Cumberland is part of a larger network of early overland travel routes in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Eastern Quebec, and Maine meant that the Ottawa House and Partridge Island were an integral part of the historical development of the entire region. The Road to Cumberland is just a small portion of a network extending from Halifax to Riviere-du-Loup on the Saint Lawrence River and on to Castine and Machias on the coast of Maine (Campbell, 2005).

This system of inter-connected routes developed because the Mi’kmaq and other aboriginal groups were able to take advantage of a naturally occurring inland transportation system comprised of waterways and overland trails. The waterways were rivers on which they could canoe during the summer months and they could move overland by portaging their canoes from one river to the next. These trails could be traveled on foot in the summer and on snowshoes after the snow arrived. Winter travel on snowshoes allowed a traveler to haul a toboggan or a tobigan (pronounced toby-gun; See subpage tobigan) laden with goods. European settlers quickly adopted the aboriginal travel routes and in time adapted them for travel on horseback and by horse and cart. The European settlers also drove cattle and sheep along some of the routes, including the Road to Cumberland.

Much of the information on Nova Scotia’s early overland transportation routes comes from early maps. Two of these maps are shown in Fig.3 and Fig.4. Additional maps can be found in the excellent publication “The Mapmaker’s Eye, Nova Scotia through Early Maps” (Dawson, 1988). To fully understand the strategic location of the Ottawa House on a network of early overland travel routes both Fig.3 and Fig.4 must be examined as well as several maps in the “The Mapmaker’s Eye”.

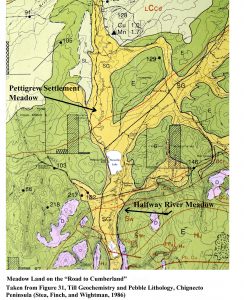

The top of Fig.3 shows two rivers separated by a narrow strip of land labeled as the “Carrying Place”. One river, labeled River Minas on the map, starts at an inland lake (Gilbert Lake) and flows north through the River Hebert valley to the Cumberland Basin. The other river, labeled River Chignecto (Partridge Island River on some early maps), also starts at another lake a short distance away (Devil’s Lake) and flows south through the “Parrsboro Gap”, a pass that cuts through the Cobequid Highlands (Stea,

From Figure 3, showing River Minas, Rover Chignecto and the Carrying Place. The rivers have since been renamed. See some current maps.

Finch, and Wightman, 1986,p.6), and on to the Partridge Island region on the Minas Basin. The “Carrying Place” is actually a geologically formed ridge separating the two lakes and it is also a drainage divide; the River Minas (now called river Hebert) flows north and the River Chignecto flows south. A photograph of this drainage divide, known as a recessional moraine, can be found on the top of page 185 of the publication “The Last Billion Years”(Atlantic Geoscience Society 2001). Also view Gilbert Lake (a subpage for this page) for current maps.

A recessional moraine is a ridge of gravel and boulders deposited during the retreat of a melting glacier from last Ice Age. In the case of the moraine at the “Carrying Place” the retreating ice formed a short portage between the headwater of two river systems: the River Hebert flowing north and the Chignecto River flowing south. When the Mi’kmaq and other Aboriginal groups arrived in Nova Scotia, they recognized the value of the glacier that had created the Minudie to Partridge Island landscape and realized its value as a waterway and as a trail across the Chignecto Peninsula.

From Fig.4, we see that as early as 1755 the English traveled over the “Carrying Place” on a route they called “The Road from Chignecto to Minas.” Map 5.2 in “The Mapmaker’s Eye” has an even earlier drawing (1735) with the route marked as the “Carrying Place from Mines to Chignecto.” As explained earlier, the final designation for the inland route across the Chignecto Peninsula was “The Road to Cumberland” or “Road from Partridge Island to Cumberland”. This selection occurred sometime after the English captured Fort Beausejour. A name for the route was necessary in order to describe land boundaries on Land Grants that were eventually issued along the road. The road name was also used in boundary descriptions on deeds written when sections of the grants were to be sold.

Both Fig.3 and Fig. 4 show the Pesaquid (present-day Windsor) to Halifax route on the south side of the Minas Basin and on Fig.4 the route has been labeled “Road from Halifax to Pesaquid. The existence of the Pesaquid to Halifax route demonstrates that it was possible to travel overland between the Fort Beauséjour/ Fort Cumberland region and Halifax. A boat or vessel would be required to cross the Minas Basin and the Ottawa House site might have been a major point of arrival or departure for this crossing.

Map 8.2 in “The Mapmaker’s Eye” states that the road from Pesaquid to Chibouctou was a “drove” road. This means that cattle and/or sheep were herded along the road. During the English period there is mention of drovers driving cattle over the Road to Cumberland. The Acadians may have driven animals along this route.

The network of overland travel routes that includes the “Road to Cumberland” has two more branches. One branch connects Annapolis Royal and Pesaquid; the other one connects with an important military communications route called “The Road to Canada” (Campbell, 2005).

The Annapolis Valley branch, as well as material on Partridge Island, is described in a small pamphlet published in 1774 that has the title “A Journey Through Nova Scotia” (DeWolfe,1997, p51 to p87; Rispin,2000). The pamphlet was written and published by John Robinson and Thomas Rispin, two farmers from York (England), who spent several months exploring Nova Scotia. A map in this publication (Fig.5) shows the Annapolis Royal and Pesaquid overland route.

Robinson and Rispin traveled over this trail from Annapolis Royal to the south side of the Minas Basin and then by water to Partridge Island. From Partridge Island they traveled over the Road to Cumberland to the Isthmus of Chignecto road and then on to Sackville Township. Their comments on Partridge Island and their description of the road to the head of the River Hebert, which they call river Bare, are interesting and informative (DeWolfe,1997, p63). They state that part of the island (the actual island called Partridge Island) is cultivated and that not far away two taverns are kept for the convenience of travelers who cross the Basin of Minas. Robinson and Rispin give the cost of the passage across the Basin and a detailed description of the Road to Cumberland. This description mentions that at some locations along the road one finds interval land, meadows, and brooks where nets can be fixed.

Some of the best agriculture land on the southern end of the Road to Cumberland is along a portion of the road where Robinson and Rispin observed the interval land and meadows (See Fig.6). It is not surprising that land grants were laid out along this portion of the Road to Cumberland in the 1770’s. The meadows on these grants were important sources of hay well into the 1930,s. Unfortunately these extensive meadows are not clearly visible from the present-day highway. One meadow, located between Gilbert Lake and Newville Lake, is now a Duck’s Unlimited wetland surrounded trees. The other meadow region is along the first mile or so of the Boars Back road. Here the meadow starts just north of Newville Lake and extend to Pettigrew Settlement, a section of this meadow is called Pettis Meadow.

At the head of the River Hebert, Robinson and Rispin found two more taverns for those going to or from Cumberland. The tavern proprietors rented horses to travelers and kept a boat. The boat likely indicates that travelers arriving at the mouth of the River Hebert required water transportation in order to cross the river. The crossing was likely between Minudie and Amherst Point (see Fig.7) and probably took place at high tide. Wading the river at low tide may not have been possible because, as Fig.7 shows, extensive salt marshes and mud flats are found in this region of the Cumberland Basin. These tidal features would make crossing such a challenge that a ferry service was required. To date I have not found records to indicate that a horse and rider or a horse drawn cart could cross by wading the river when the tide was out. Two stories, reproduced in Accounts by Travellers (a subpage to this page) confirm that a ferry was necessary.

A route that crosses the Isthmus of Chignecto connects Amherst Point, Fort Lawrence, Fort Cumberland, and Sackville Township. A traveler could leave Nova Scotia and reach such distant places as Riviere-du-Loup on the Saint Lawrence River and Castine and Machias on the coast of Maine. The importance of these routes to the First Nations, the Acadians, and the English is well documented in the publication ‘The Road to Canada: The Grand Communications Route from Saint John to Quebec” (Campbell, 2005). This excellent book describes many of the historically significant events that took place on these overland routes, including the Eddy Rebellion (Campbell, 2005,p 36). This attack on Fort Cumberland by Jonathan Eddy occurred in 1776 and it is believed that during the siege, Eddy had a military tactic that involved sending several of his men to Partridge Island.

Geology and Land Grants

The major geological formations along the Road to Cumberland may have influenced a wide range of human activities, including the way in which the early settlers worked and traveled in that region. These formations were both beneficial and a source of problems. They enabled the settlers who lived along the Road to work at agriculture and lumbering and settlers living in the coastal area were involved in fishing, shipbuilding, and seafaring as well as farming and lumbering. The problems were seasonal flooding of the fertile low lands along the road and erosion at certain coastal regions such as the site of the Ottawa House. The influence that landscape formations have on human activities is a broad subject and will only be briefly mentioned. The influence of geological formations on the placement of land grants will be emphasized.

When the governor of Nova Scotia and his council granted land in a particular region of the province they issued a “warrant to survey” to the provincial Surveyor General. The Surveyor General, or one of the deputies, was then responsible for deciding the specific location and boundaries of the grant or grants to be issued when the survey work was completed. On the Road to Cumberland the governor issued grants over a period of time but only a few grants were issued along the northern portion of the road. These tended to be very large lots of land granted to prominent individuals. Examples include the 8000 acres at Minudie granted to J.F.W. DesBarres in 1765 and 20000 acres on the River Hebert given to Michael Francklin(Crown Land Information Management Centre,1765) in 1765. Joseph Frederick Wallet DesBarres was an army engineer and surveyor; Michael Francklin was a Halifax merchant who became lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia in 1766.

Along the southern section of the Road to Cumberland the provincial surveyors laid out many long narrow strips of land with each strip being a possible grant; some settlers received more than one strip. This section of the route is of particular interest to the history of the settlement at Partridge Island and to the later settlements that formed along the road from Partridge Island to Pettigrew Settlement. It is this southern section of the route that will be the major focus of this paper. The remainder of the route will be only briefly mentioned.

Fig. 8. Geomorphic provinces of the Lower Minas Basin. Taken from the article “A Raised Fluviomarine Outwash Terrace, North Shore of the Minas Basin, Nova Scotia”, by Donald J. P Swift and Harold W. Borns, Jr., Journal of Geology, V 75, 1967, p 693

A traveler approaching Partridge Island from the water would see a natural coastal formation created by a series of complex processes at the end of the last Ice-Age (Donald J. P Swift and Harold W. Borns, Jr., 1967 and Atlantic Geoscience Society 2001, Chapter 9). This formation, extending from Advocate to Five Islands (see Fig.8) and composed of silt, sand, gravel, and boulders, is called a “raised outwash terrace”. At Partridge Island the Chignecto River eventually cut through the terrace to form an estuary (present day Parrsboro Harbour). The north-south orientation of this estuary was selected by a provincial land surveyor to be the dividing line between what are believed to be the first two land grants in this part of the Minas Basin. The ferry would have landed on the beach in front of one of these grants.

The Outwash Terrace in the vicinity of Parrsboro. Screen capture from A Virtual Field Trip of the Landscapes of Nova Scotia with Dr. Ralph: Vista 3: Parrsboro Delta and Glaciated Valley. (Nova Scotia Lands & Forestry) View Vista 3 for more images related to the Road to Cumberland.

At the end of the 1760’s, the flat top of the terrace in the Partridge Island region and on the western side of the estuary must have caught the attention of provincial deputy land surveyor Josiah Troop. At the end of this decade Troop and several other provincial surveyors laid out two large tracts of land known as the Partridge Island Grant and the Philadelphia Township Grant. The 2000 acre Partridge Island Grant was located on the western side of the estuary and the 20000 acre Philadelphia Township Grant, issued in 1767 to Nathan Shepherd and nineteen others from the City of Philadelphia, began on the eastern side of the harbour and extended eastward along the coast to Five Islands (Crown Land Information Management Centre. 1767).

Fig 9. Position of the Partridge Island Grant on the Road to Cumberland. Taken from Index Sheet # 51 Map held at the Crown Land Information Management Centre, 1701 Hollis Street, Halifax.

https://novascotia.ca/natr/land/grantmap.asp

The Partridge Island Grant was issued in 1776 to John Avery, Jacob Bacon and John Lockhart with the proviso that they run a ferry. However, Troop’s drawing (Fig. 9) for this grant is dated 10th March 1767 (1769?) and is divided into town lots and field lots. This complexity is not what one would expect a surveyor to lay out for three men operating a ferry! Josiah Troop’s plan for the Philadelphia Township Grant, located in an archival collection at the Pennsylvania Historical Society, is dated at Partridge Island on September 14, 1767 (Wright, 1977, p.117-118). The dates on these two surveyor’s maps lead one to wonder if the land laid out on the raised terrace at present day Parrsboro was initially intended for a group other than Avery, Bacon and Lockhart.

Fig. 10: 1767 (1769?) Surveyor’s Drawing for the Partridge Island Grant. Cumberland County Portfolio, Crown Land Information Management Centre, 1701 Hollis Street, Halifax

Fig.9 (above) shows the position of the Partridge Island Grant on the Road to Cumberland and Fig. 10 is the 1767 (1769?) surveyor’s drawing for this grant.

The long narrow strips of land on this plan front on the Chignecto River and are probably so-called “town lots”. Most or all of these lots are on the raised outwash terrace. At Partridge Island the portion of the raised terrace on which the Ottawa House sits faces the open Minas Basin and is therefore is subject to erosion during stormy weather.

As with most grants, the Philadelphia Township was issued with conditions that had to be meet within a defined time period. When grant conditions are not complied the land reverts back to the Crown and the grant is said to have been escheated. On March 9, 1784 the Commissioner of Escheats, Richard Bulkeley , and twelve jurors made the decision to escheat the Philadelphia Township Grant (Crown Land Information Management Centre, Escheat #66). Two exceptions, involving the settlers Steven Harrington and Jacob Walton, were written into the escheat document. Harrington and Walton had acquired land in the Township and because they had made improvements that fulfilled the grant conditions their properties were not included in the escheat. To date a copy of the surveyor’s drawing for the Philadelphia Township Grant has not been located; however, the grant issued for the Philadelphia Township does describe the boundaries of the Township.

Moving inland a short distance the Road to Cumberland begins to pass through the Cobequid Highlands (The Last Billion Years, p. 67) by way of the “Parrsboro Gap” (Stea, Finch, and Wightman, 1986,p.6). On leaving this Pass, one encounters Gilbert Lake, the headwater for River Hebert, and Devil’s Lake, the headwater for the Chignecto River; these two lakes are separated by the recessional moraine described earlier. In the time of travel by canoe this ridge of glacial till, indicated by “Carrying Place” on Fig.2 and Fig.3, was a portage between the north flowing River Hebert and the south flowing River Chignecto.

From Gilbert Lake, the Road to Cumberland lies on the so-called Cumberland-Pictou Lowlands (Stea, Finch, and Wightman, 1986, Fig.1, p.3). As described in the previous section, it is on these lowlands that Robinson and Rispin observed the interval land and meadows (see Fig.6 above). Just north of Newville Lake and moving down the River Hebert the Road moves past Pettigrew Settlement and onto the “Boars Back”, a long ridge of glacial till called an esker (Stea, Finch, and Wightman, 1986,p.25). The overland trail portion of the Road to Cumberland went along the top of this ridge and the waterway portion was the River Hebert, which flows close to and adjacent to the “Boars Back” esker.

The start of the “Boars Back” esker is the approximate divide between two land grant patterns on the Road to Cumberland. This divide is also the boundary line that existed between Kings County and Cumberland County from 16 Dec. 1785, when the Governor and Council changed the boundaries of Kings County, until 1840 (Fergusion, 1966, p.43). On the north of the boundary one finds the 8000 acres at Minudie to J.F.W. DesBarres in 1765 and 20000 acres on the River Hebert to Michael Francklin in 1765. The process by which these two grants were eventually subdivided and placed in the hands of others is a separate topic that needs to be thoroughly researched.

Fig 11. Grant lots on the Road to Cumberland from the Mouth of the Chignecto River to Francklin’s Manor, Cumberland County Portfolio, Crown Land Information Management Centre, 1701 Hollis Street, Halifax

Fig.11 shows the surveyor’s map for the portion of the Road to Cumberland that lies south of the dividing line. The date of this Charles Morris map is uncertain, the date at the top appears to be 1774 or 1784. Notice that this grant begins on the east side of the estuary at the mouth of the Chignecto River and has one branch of 33 divisions that are laid out along the coast as far as Five Islands. 1784 is a possibility because 1784 is the year that the Philadelphia Township Grant was escheated. The 33 lots along the bottom of Fig 10 represent a redrawing of the 20 Philadelphia Township Grant lots that are mentioned in the 1767 grant that was issued for the Philadelphia Township.

Notice that the front of each lot on Fig.11 borders on the water. This was essential in the days when water was an important means of transportation. An effort appears to have been made to place the lots in the valley formed in the Cobequid Highlands by the Parrsboro Pass and that north of the Cobequid Highlands the lots are along the valley formed by the river Hebert. The land surveyors who were given the task of laying out grants for settlers must have had an eye for taking advantage of landscape geology.

As mentioned earlier the geological formations on the Road to Cumberland were formed by a series of complex processes at the end of the last Ice-Age. This sequence of events is called postglacial geology, one of the many sub-fields of geology. The bedrock beneath the Road to Cumberland’s glacial formed landscape is also interesting but is however, beyond the scope of this paper. Material on the bedrock geology can be found in the publication “The Last Billion Years”.

One more landscape feature of this overland travel route needs to be described. This is a tidal estuary formed approximately the last 6300 years (Amos, 1978, P 965-981) at the mouth of each of the route’s two rivers. The salt marshes on the upper reaches of these estuaries were a source of salt marsh hay for both the Acadian and the English settlers. The salt marshes on both sides of the River Hebert were dyked but evidence of dyking at Parrsboro has not been located. Unlike the mouth of the River Hebert a barrier beach (spit) protects the mouth of the Chignecto River and when the tide is in, the lagoon that forms behind this coastal barrier provides Parrsboro with a deepwater harbour.

References

Atlantic Geoscience Society 2001. The Last Billion Years , A Geological History of the Maritime Provinces of Canada, . Halifax, Nova Scotia, : Nimbus Publishing Ltd

Barss, Peter. 1980. Older Ways:Traditional Nova Scotia Craftsmen. Toronto: Van Nostrand RVan Nostrand Reinhold Ltd.

Campbell, Gary. 2005. The Road to Canada: The Grand Communications Route from Saint John to Quebec ,New Brunswick Military Heritage Series 5. Fredericton, New Brunswick: Goose Lane Editions:New Brunswick Military Heritage Project.

Conrad, Margaret, ed. 1988. They Planted Well: New England Planters in Maritime Canada. Fredericton, New Brunswick: Acadiensis Press.

Crown Land Information Management Centre. Dept. of Natural Resources, Halifax, NS.,. 1765. Book 006, page 329, and Book 006, page 716.

Crown Land Information Management Centre. Dept. of Natural Resources, Halifax, NS.,. 1767. Grant Book 006, page 703 and Grant Book 007, page 238.

Crown Land Information Management Centre. Dept. of Natural Resources, Halifax, NS.,. 1784. #66 KERR PLS FIX

Dawson, Joan. 1988. The Mapmaker’s Eye, Nova Scotia Through Early Maps. Halifax: Co-published by Nimbus Publishing Limited and The Nova Scotia Museum, .

Deveau, Sally Ross and J. Alphonse. 1992. The Acadians of Nova Scotia Past and Present. Halifax, Nova Scotia: Nimbus Publishing Ltd.

DeWolfe, Barbara. 1997. Discoveries of America : personal accounts of British emigrants to North America during the revolutionary era. New York Cambridge University Press.

DeWolfe, Barbara. Discoveries of America : personal accounts of British emigrants to North America during the revolutionary era. Cambridge University Press 1997 [cited February 15, 2010. Available from http://www.cambridge.org/uk/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9780521385428.

Donald J. P Swift and Harold W. Borns, Jr. 1967. A Raised Fluviomarine Outwash Terrace, North Shore of the Minas Basin, Nova Scotia. Journal of Geology 75: 693-710

Fergusson, Charles Bruce. 1966. The Boundaries of Nova Scotia and its Counties. Bulletin of the Public Archives of Nova Scotia, No22. Halifax: Public Archives of Nova Scotia.

Graham, Hugh. Acadian French: Letter from Rev. Hugh Graham to Rev. Brown 1791 [cited Febuary 13, 2010. Available from http://www.gov.ns.ca/nsarm/virtual/deportation/archives.asp?Number=NSHSII&Page=129&Language=English.

Murphy, J. M. 1976. The Londonderry Heirs: A Story of the Settlement of the Cobequed Townships of Truro, Onslow, and Londonderry, in Nova Scotia, Canada, by English-Speaking People in the Period 1760 to 1765. Middleton, Nova Scotia: Black Printing Co. Ltd.

Parker, Mike. 2009. Gold Rush Goast Towns of Nova Scotia. East Lawrencetown, Nova Scotia: Pottersfield Press.

Rispin, Charlie. 2000. Thomas Rispin Farmer of Fangfoss East Yorkshire [cited February 12, 2010. Available from http://www.rispin.co.uk/farmer.html.

Stea, R. R., P. W. Finch, and D. M. Wightman. 1986. Quaternary Geology and Till Geochemistry of the Western Part of Cumberland County, Nova Scotia (Sheet 9). In Geological Survey of Canada, Paper 85-17

Wright, Esther Clark. Cumberland Township: A Focal Point of Early. Settlement on the Bay of Fundy 1946 [cited February 12, 2010. Available from http://atlanticportal.hil.unb.ca:8000/archive/00000091/01/wright.pdf.

Wright, Esther Clark. 1977. Blomidon Rose. Wolfville, Nova Scotia.